April 13, 2024 | The European Conservative | By Harrison Pitt

The return of Schmitt is no cause for panic.

There can be no doubting the fact that a revival of dissident Right literature is afoot. At a time when a protracted culture war is pitting the natural conservative against the very institutions he desires to love, perhaps it was inevitable that the heartfelt reflections of Burke and Scruton would have to be supplemented—if not altogether replaced—by the hard-headed realism, even the tactical dark arts, of forgotten names like James Burnham and Sam Francis.

The most impressive figure to emerge from this drastic shift, the undisputed king of the radical Right Renaissance through which Anglo-American conservatives, accustomed to gentler wisdom, find themselves living, is Carl Schmitt. He also happens to be the most volatile.

Hitler’s Crown Jurist?

The good news is that the main works for which Schmitt is justly esteemed were written before the rise of Hitler. They can therefore be considered independently of the fact that in May 1933, on the same day as Martin Heidegger as it happens, Schmitt officially joined the Nazi Party. Due to his first-rate legal mind and professed ideological sympathies, he was even something of an intellectual favourite among the more philosophically inclined of these psychotic gangsters.

This changed in 1936, when a Schutzstaffel (SS) rag by the name of Das Schwarze Korps, probably with just cause, hurled charges of opportunism Schmitt’s way, pointing in particular to occasions in the 1920s when he had attacked the Nazis for their obscene racial theories.Schmitt had also been among those who, at the height of the crisis of the Weimar Republic, tried to convince President Hindenburg to invoke the dictatorial powers conferred by article 48 against all political actors intent on overturning the post-war order, from Hitler’s brownshirts to Bolshevik-style communists. If anything, the thrust of Schmitt’s critique of Weimar, laid out in The Crisis of Parliamentary Democracy (1923), was that, beholden to a suicidal faith in unconditional openness, political liberalism lacked the resources to defend itself.

Schmitt was duly investigated for his track record of suspected thought crimes, but Hermann Göring—an admirer and perhaps the most intelligent high-ranking Nazi—was successful in preventing such queries from leading anywhere fatal. Spooked by what he would later refer to as “the legal, semi-legal and illegal means of power employed by the SS and the circles around Himmler,” Schmitt spent the remainder of this nightmarish chapter in history engaged in more abstruse academic pursuits, such as the formulation of an anti-American ‘Monroe Doctrine’ for Europe, understood wholly in terms of the self-defined geopolitical interests of the Reich.

While Schmitt has been dubbed “Hitler’s Crown Jurist,” it is a stretch to argue that the Nazi state possessed any coherent concept of law, let alone one in need of systematic justification.Despite initial plans to replace the existing criminal code, in the end this undertaking was abandoned. The Nazis were suspicious of the very notion that law should be consistent, codified, and available to those subject to its commands. “Hitler,” explains the historian Michael Burleigh, “regarded written rules as potentially restrictive of his capricious will.” Still, Schmitt cannot be excused for lending ballast to such lawless tyranny. After the Night of the Long Knives, he published an article celebrating the boldness with which the Nazis had clamped down on their enemies:

The Führer protects the law against the worst forms of abuse when, in the moment of danger, he immediately creates law by force of his character as Führer as the supreme legal authority.

In any case, this Führerprinzip (‘Führer principle’) held that not only what pleases the prince, but what the supreme leader thinks from moment to moment, has the force of law. Even Hitler’s most impulsive musings could be enforced, retrospectively as well as into the future. To suggest that such a theory needed talented lickspittles like Schmitt to reinforce its authority with philosophical argument is anathema to the totalitarian nature of the principle itself. Schmitt disgraced himself as an apologist, but he could never have been a legal architect, the crown jurist, of a Nazi regime that had no time for law as conceptually understood.

The return of Schmitt is no cause for panic. The revival has more to do with his brilliant insights, most of them spread across works written in the decade from 1922-32, than his later association with Nazism. There are three major reasons for the renewed interest. First, we have the growing sense that 21st century democracy is a sham. Second, there is a related urge to comprehend our slide into murky, bureaucratic forms of governance. Last of all, a re-examination of the increasingly implausible belief that institutions, whether directly or indirectly linked to the state, can be perfectly neutral is underway. As a gifted critic of liberal democracy who touched on all of these urgent themes, Schmitt is impossible to neglect.

The Sham of Liberal Democracy

Schmitt was no opponent of democracy as such. What he attacked was the cult of democracy in its liberal, so-called “parliamentarist” form. The liberal’s faith in the parliamentary model, based on the ideal of a “discussing public” that is both eager and qualified to make political decisions, he regarded as a sentimental illusion. In practice, this discussing public, insofar as it even exists, is bound to have its preferences distorted by a smaller set of oligarchic interests. Well-organised minorities will always command an outsized influence over what goes on in centres of alleged people-power. “Small and exclusive committees of parties or of party coalitions,” Schmitt observes in The Crisis of Parliamentary Democracy, “make their decisions behind closed doors, and what representatives of the big capitalist interest groups agree to in the smallest committees is more important for the fate of millions of people, perhaps, than any political decision.”

When, critics may protest, has some version of what Schmitt describes not been the case? According to the conventional wisdom represented by Churchill’s famous quip, democracy might have its flaws, but is it not the worst political system except for all the others? The problem is that the liberal democrat claims to have made a glorious break with all prior history. If Schmitt’s red-pilling polemics succeed in exposing that the people do not in fact rule, he has achieved his purpose.

At a time when our elites continue to import new immigrant voters not only without the consent of existing voters, but in clear defianceof their wishes as expressed consistently at the ballot box, who can really argue that the British people rule Britain or that Americans are in charge of the United States? “In the face of this reality,” Schmitt proclaims, “the belief in a discussing public must suffer a terrible disillusionment.” What we today call ‘populism’ is best understood as an apoplectic impulse to set right the failures of democracy by voting the ideal back into reality—in most cases quixotically and without a solid grasp of why the democratic promise broke down in the first place.

An Impotent Discussing Class

Likewise, Schmitt does not challenge the existence of elites as such, but rather their pretence under democratic systems to have relinquished power and distributed it equally among the people.The crisis of parliamentary democracy, he explains, springs from “the contradiction of a liberal individualism burdened by moral pathos and a democratic sentiment governed essentially by political ideals.” There is a thoroughgoing conflict, in other words, between the liberal cult of the individual and the democratic cult of the people. While the liberal’s instinct is to refer every question to a talking shop in which the right to disagree is sacrosanct and the prospect of a decisive outcome incipiently threatening, the demos—driven, as Schmitt puts it, by “political ideals”—typically has a positive vision of what it wants. Far from an end in itself, discussion is valued as the means by which these popular preferences can be made known and acted upon.

One of the issues we face today is that, while the progressive Left has no time for the talking shop, having instead succumbed to a messianic sense of moral purpose, the Right is still expected to refrain from treating politics as a battlefield for the potential victory of its ideals. Economic liberals posing as conservatives are little more than the obedient creatures of this lop-sided dynamic, trusting in the amoral mechanisms of a deregulated market—just as the political liberal puts his faith in ‘the marketplace of ideas’—rather than mustering the self-confidence to make decisions themselves. Liz Truss has taken to complaining about the ‘politicisation’ of the treasury, the Blob, and the establishment in general, but to protest the existence of politics in Westminster is about as dim-witted as crusading against the profit motive on Wall Street. If Truss had not deified the free market as a substitute for having to think about politics, perhaps hiring some astute Schmittians as advisors instead of IEA boffins, she might have lasted a little longer.

Precisely because talking shops yield minimal results and decision-making is essential to politics, there is a tendency under regimes that call themselves liberal and democratic for power to be outsourced to bureaucracies stuffed with every species of technical specialist. An anti-political cult of expertise replaces the old-fashioned virtues of moral conviction and personal leadership.

The evidence is ubiquitous, but a recent example that springs to mind is the case of the UK defence secretary, Grant Shapps, commissioning a pointless report into the self-defeating crusade against white men in the British armed forces. A more resolute leader, trusted with the small task of defending the realm, would have simply abolished DEI within his department on clear-cut patriotic grounds. However, the “moral pathos” of liberalism, as Schmitt put it, means that—at least for nervous liberals pretending to be stalwart conservatives—technocratic approval must be sought not only before public opinion is consulted, but in lieu of its being consulted. After all, the “woke nonsense” into which Shapps has now ordered a review succeeded in capturing Whitehall without anyone being asked whether they wished to see the native male population, upon which all successful armies ultimately depend, purged from the military in the first place. If liberal democracy means the maximal possible identity of ruler and ruled, it manifestly fails to deliver the goods under the current system.

Here Schmitt diverges from the sociologist Max Weber who, following in a German tradition begun by Hegel’s hymns to the men of Bildung who would make up the “universal class” of the rational state, had hailed the modern age of technocrats. Given the shortcomings of the liberal discussing class, Weber praised bureaucracies for their “technical-rational” capacity to produce an impersonal rules-based order, the dangerous alternative being a regime founded on the all-too-personal commands of a “charismatic” sovereign. Schmitt rejected this optimistic faith, then dominant in jurisprudence, that all personal elements could be removed from the state. Such forlorn hopes, he held, stemmed from the liberal myth of neutrality in human affairs.

The Mirage of Neutrality

It is equally an illusion of our time to expect institutions, whether connected to the state or otherwise influential, to be as neutral as the Weberian accolade “technical-rational” suggests. Neutrality is a feature of liberalism that has only grown more pronounced in the last fifty years, particularly in the United States through the influence of John Rawls and Ronald Dworkin. Yet the very concept was attacked by Schmitt in the most withering terms. He saw it as proof that liberalism is a glorified species of moral paralysis, a fear of definitive judgement posing as firm principle.

In Political Theology (1922), he praises Juan Donoso Cortés, the Spanish counter-revolutionary thinker, in defence of this judgement. Cortés, he claims, was rightly hostile to la clasa discutidora, the liberal discussing class, viewing their relentless chatter and their claim to neutrality as

a method of circumventing responsibility and of ascribing to freedom of speech and of the press an excessive importance that in the final analysis permits the decision to be evaded. Just as liberalism discussed and negotiated every political detail, so it also wants to dissolve metaphysical truth in a discussion. The essence of liberalism is negotiation, a cautious half measure, in the hope that the definitive dispute, the bloody decisive battle, can be transformed into a parliamentary debate and permit the decision to be suspended in an everlasting discussion.

There is the further point, as we have already seen, that such deferral cannot go on forever. The essence of politics is decision-making. Those who seek to avoid it, whether by taking refuge in never-ending debate or off-grid quietism, will have the most important decisions made for them. Entrusting supposedly neutral, “technical-rational” bureaucracies with the power of decision-making is one possible outcome, but there is also the ever-present danger that a more fervent ideological agenda, less afraid of “the decision,” will either assert itself within the talking shop or capture the very bureaucracies to which nervous liberals have surrendered power.

These two weaknesses come together in the idea of a ‘heterodox’ institution. Liberals who adore free speech as an end in itself are bound to be manipulated by those who see it as at best an instrumental good, a convenient means by which to accomplish their objectives. A complacent commitment to heterodoxy within an institution will be weaponised by bad faith actors intent on enthroning their own prejudices as the new orthodoxy. This can only be avoided, as we shall examine more generally in due course, if the commitment to heterodoxy is bolstered by a more fundamental set of non-negotiable orthodoxies, some supporting core principles which help to insure the institution against manipulation and capture. But once the commitment to heterodoxy is put on solid foundations, the body ceases to be neutral in any perfect sense, for the body in question cannot afford to be neutral about whether these foundations remain solid or are left to crumble.

The critique is best developed in The Concept of the Political (1932). Discussing global politics, but also alluding to the domestic kind, Schmitt argues that neutrality assumes conflict:

As with every political concept, the neutrality concept too is subject to the ultimate presupposition of a real possibility of a friend-and-enemy grouping. Should only neutrality prevail in the world, then not only war but also neutrality would come to an end. The politics of avoiding war terminates, as does all politics, whenever the possibility of real fighting disappears.

In other words, if there is a real site of conflict in the world, neutrality is indistinguishable from indifference. But if no such conflict is raging, or the need to start one is not felt, there is nothing to be neutral about and, as such, talk of neutrality is unintelligible. It either presupposes existing controversy or anticipates future controversy. Neutrality, to invoke a term of art from the philosophy of mind, is an intentional state. It is not unconscious, but necessarily directed towards some object. In the midst of a culture war, when everything in a civilisation—from its heroes to its right to exist—is up for grabs, maintaining some liberal commitment to neutrality is at best cavalier and at worst negligent.

Loyalty to some X always lurks behind neutrality as regards some Y. In this case, the liberal’s loyalty to the ideal of limited government—which, after all, is not neutral at all, but a stance that must be actively defended against those who wish to moralise the state’s functions—lurks behind his neutrality towards whatever questions he believes to be so fundamental that individuals must be free to decide the answers for themselves. The point is that neutrality in itself is a vacuous concept. No one is neutral about everything: even a man who professes neutrality as to whether he lives or dies cannot be neutral in an argument between, say, a Christian and a naturalist over whether human life is sacred. He has no choice but to side with the naturalist, for siding with the Christian would undercut his claim to neutrality concerning the question: ‘to be or not to be?’

In effect, ‘neutral about X’—and it must be about something, for no one is neutral in the abstract—is just a self-flattering way of saying ‘indifferent to X.’ But there must always be a reason for said indifference. And he who affirms indifference to X cannot be neutral in the face of his own reasoning, otherwise whatever he ponies up in support of his indifference would cease to count as a reason. He must remain loyal to the reason or his grounds for neutrality give way. Therefore, any intelligible claim to neutrality in a particular respect is predicated on partiality in another more vital respect. Those on the Right who, intoxicated by the strength of Schmitt’s claims, assert that it is impossible for institutions or the individuals within them to be neutral are therefore mistaken. If never in an absolute sense, neutrality is still practicable in all sorts of limited ways. In any given case, however, neutrality must be directed towards something and will inevitably come attached with a prior, more fundamental version of its opposite: loyalty. To repeat, positive belief in some X always underpins neutrality to some Y.

Friend and Enemy

If people know anything about Schmitt it tends to be that he conceived of politics in fairly zero-sum terms. This distinguishes him from those in the Western tradition who have felt moved to tame tribalism by reference to higher principles. Yet, contrary to any talk of building some universal moral order, Schmitt maintains:

The specific political distinction to which political actions and motives can be reduced is that between friend and enemy.

To the Hobbesian state of war among individuals, observes Leo Strauss in his commentary on The Concept of the Political, Schmitt opposes the state of war among groups. At any one time, the fault lines dividing friend from enemy may differ, both in terms of content and geography. “Every religious, moral, economic, ethical, or other antithesis,” writes Schmitt, “transforms into a political one if it is sufficiently strong to group human beings effectively according to friend and enemy.” The existence of the political in a given sphere of human life is not guaranteed, but it is an ever-present possibility. Newly politicised spheres should not be cursed, still less ignored. For anyone who cares, the only choice is to contest them on these radically altered terms, however regrettable. The reach of the political knows no bounds and its dynamics cannot be extinguished. Certainly when we include geo-strategic concerns, the reality of politics is ineradicable:

If a people no longer possesses the energy of the will to maintain itself in the sphere of politics, the latter will not thereby vanish from the world. Only a weak people will disappear.

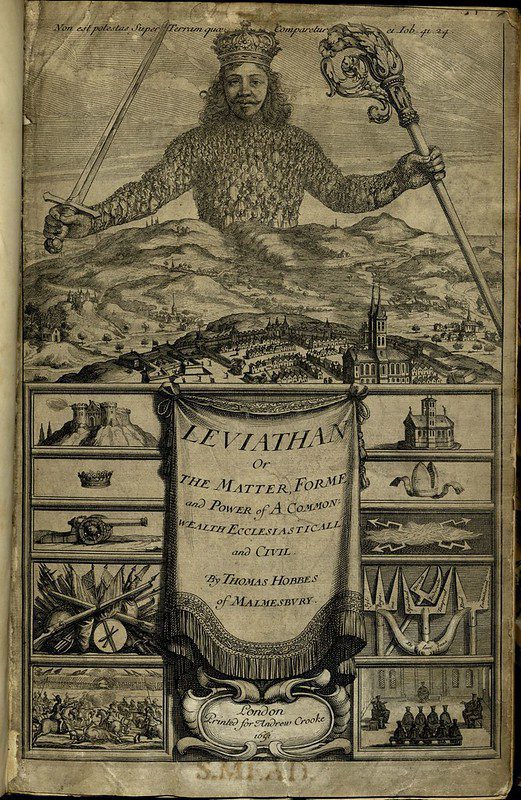

Of course, such enmity can also cause strife within countries. It was for this reason that Schmitt considered civil wars the mother of clarity. Despite the fact that much of Hobbes’s Leviathan (1651) had been canvassed in unpublished manuscripts written before the violent chaos that reigned in the British Isles from 1642 onwards, Schmitt credits the English Civil War with bringing out the best in this 17th century giant. It is under such volatile conditions, he explains, that “all legitimate and normative illusions with which men like to deceive themselves regarding political realities in periods of untroubled security vanish.”

Nevertheless, there is an implicit concession here that “periods of untroubled security” do exist, even if the dangers of entropy and dissension lurk in the background. Contrary to his more zealous disciples, who are loath to mistake unremitting cynicism for a kind of heroically reptilian, ever-reliable insight, Schmitt would have granted that shared virtues and settled habits can serve to pacify fundamental areas of potential dispute, almost always within a nation, in a way that weakens the salience of the friend-enemy distinction—at least for a time. Britain was once the obvious example, so much so that Schmitt himself was fond of quoting from Lord Balfour’s introduction to Walter Bagehot’s The English Constitution (1867):

The whole political machinery presupposes a people so fundamentally at one that they can safely afford to bicker; and so sure of their own moderation that they are not dangerously disturbed by the never-ending din of political conflict.

However, unless there exists a widely accepted bias in favour of these rules of the game, quite apart from whether they always benefit your team, the competitive aspect of politics will produce a situation in which either parties or charismatic individuals seek to integrate themselves into the state. As we saw earlier, constitutions cannot be both authoritative and neutral: a constitutional order cannot hope to maintain its authority if, lacking faith in itself, it forfeits its duty—or even renounces its right—to favour friends over sworn enemies of the order.

From the fact that these enemies are scarce enough to be politically irrelevant at a particular moment it does not follow that they will always be so. If Schmitt’s most passionate adherents are wrong to hail the friend-enemy dichotomy as a universal rule, those who denounce such cynicism in equally universal terms are resting on ground more precarious even than their own laurels: the rare luxuries of historical contingency. Unless some minimum of friendship, rooted in a cohesive demos and an easy-going moral unity, forms the basis of the polis in the way that Aristotle recommends, internal divisions will increasingly take on the zero-sum dynamic made infamous by Schmitt. The positive grounds of neutrality, found to be necessary earlier, will give way.

Der Ausnahmezustand: Can Law Truly Rule?

In much of the above, there is an implied critique of the rule of law. Schmitt was not shy about making it explicit.

Prior to the First World War, he subscribed to an idealist conception of the state which held that justice exists prior to manmade legal systems. Positive law is thus an inadequate copy of its ideal, and may even forfeit its status as law altogether, if it fails to reflect this moral order. He later came to embrace the more recognisably Schmittian maxim of Thomas Hobbes: autoritas, non veritas, facit legem—authority, not truth, makes law.

First, we should deal with one of Schmitt’s weaker efforts to discredit the rule of law. This occurs in The Concept of the Political where, as if anticipating the need to demolish the more misguided liberals of the later 20th century, Schmitt labours under the implausible assumption that the rule of law is no different from the ideal of a neutral state:

Law can signify here the existing positive laws and law-giving methods which should continue to be valid. In this case the rule of law means nothing else than the legitimation of a specific status quo, the preservation of which interests particularly those whose political power or economic advantage would stabilize itself in this law.

Needless to say, the references to “political power” and “economic advantage” are meant to deal a fatal blow to the concept. The problem is that there are three main criteria for a law-governed society to exist, none of which has anything to do with unconditioned neutrality. First, public servants can exercise no power that is not expressly granted to them by the law. Second, the law must apply equally to every person residing within a territory. Finally, only independent judges—whose loyalty to the existing procedures, to repeat the formula for neutral states of mind outlined earlier, must underpin their impartiality to the politics of any particular case that comes before them—are entitled to interpret the law in a binding way. The fact that the law is smudged by human fingerprints does not imply the physical or logical impossibility of any of these principles. Law can be bad and still govern.

Schmitt is on stronger ground when he takes his cues from Hobbes, arguing that authority is not so much derived from law, as the liberal disciples of a figure like Locke would want to argue, as the vital precondition of law. In Political Theology, Locke’s understanding is pilloried:

He [Locke] did not recognize that the law does not designate to whom it gives authority. It cannot be just anybody who can execute and realize every desired legal prescription. … Accordingly, the question is that of competence, a question that cannot be raised by and much less answered from the content of the legal quality of a maxim. To answer questions of competence by referring to the material is to assume that one’s audience is a fool.

Hobbes is then applauded for making an argument that links the “decisionism” underlying legal prescriptions with the “personalism” embodied by the figure of Leviathan. The attempt by liberal constitutionalists to severe personhood from authority, typically by resort to such language as “a government of laws, not of men” (still less one man), is written off as a non-starter.

While he did not live to see the end of the Cold War, Schmitt must have known that his view would trigger doubts among the more passive citizens of apparently law-governed democracies. Whatever vindication he might feel now that the triumphalism of 1991 has passed, leaving liberals baffled and miserable, in response to anyone who might still point to the modern West as a testament to the purring efficiency of the rule of law Schmitt would want to stress that any such optimism is a surface-level analysis, fostered by what I earlier described as the rare luxuries of historical contingency. For Schmitt, der Ausnahmezustand, best translated as “the state of exception,” is the real test of whether law can serve as the ultimate governing force in a society. And since law is causally effete, only a person or a group of persons possess the agency to decide from moment to moment whether a state of exception is at hand:

For a legal system to make sense, a normal situation must exist, and he is sovereign who definitely decides whether this normal situation actually exists.

Exceptional cases reveal the locus of sovereignty. And crucially, because exceptions are not predictable in advance, they cannot, as Schmitt stresses, be “prescribed in the law.” This is the essential import of the emphatic opening line to Political Theology: “Souverän ist, wer über den Ausnahmezustand entscheidet”—sovereign is he who decides the state of exception. The liberal constitutionalist, clinically averse to the notion that anything other than law is sovereign, has no answer. All he can do, according to Schmitt, is keep up the illusion that a written legal order can truly rule with rhetoric like ‘government under law’ or ‘checks and balances’ until an exception destabilising enough to shatter it duly does so.

Law is not an independent authority, but the work of an author whose all-too-human qualities we only glimpse when the real source of authority decides that normality has been outpaced by events. This occurs when the present contents of the law are so ill-suited to an unforeseen emergency that extra-legal action is taken by its latent, if temporarily forgotten, master—this authority residing, as Schmitt is eager to emphasise, “always outside the law.”

Of course, the liberal constitutionalist will point out that there is a considerable body of literature discussing how law-governed societies should cope when disaster strikes. Even Friedrich Hayek, arguably the finest classical liberal of the 20th century, accepted the possible need to suspend freedoms during emergencies, albeit with firm provisions for ensuring their swift reinstatement once the crisis has passed. Possibly even alluding to Schmitt, at one point in The Constitution of Liberty (1960) Hayek notes:

‘Emergencies’ have always been the pretext on which the safeguards of individual liberty have been eroded—and once they are suspended it is not difficult for anyone who has assumed emergency powers to see to it that the emergency will persist.

However, any cast-iron guarantees that such abuses cannot happen as a matter of law will have to be statutory. If not, Schmitt’s argument that extra-legal factors decide the state of exception wins the day. Yet, if so, Schmitt is a step ahead of his critics. He explains that by seeking to debunk the notion of a law-governed society, he does not mean to suggest that “legal decisions are independent of statutes or other texts.” The point, he continues, is that even in cases where the sovereign, in addressing a state of exception, wants to uphold the appearance of legality, “whichever statute, text, precedent, or other referent will be chosen cannot be determined entirely in advance.”

Recent history seems to vindicate this. Nothing stopped the British government from dubiously invoking the ultra-permissive Public Health Act, rather than the much more constraining Civil Contingencies Act, to lock everyone in their homes for indefinite periods of time with minimal parliamentary scrutiny. The tyranny of the COVID era proved at the very least that the rule of law, where it can operate, is an exceedingly fragile achievement. Even if extra-legal considerations do not invalidate the rule of law’s claim to existence, they certainly make that existence a contingent matter. Not only the absenceof emergencies, but a strong public feeling in favour of weathering them in a way that preserves freedom under law is an essential ingredient. So, we might add, is a shared sense of identity, heritage, and religion. Law does not tend to rule so much as power and brute numbers in those countries most blessed by religious, ethnic, and linguistic diversity.

However sublime in theory, favourable conditions, both material and spiritual, are required for law to rule in practice. Legality is no substitute for God, but this is distinct from saying that it is impossible. Hobbes was right to argue that any godlike qualities that the state possesses are in fact the “mortal” stamp of human design. As such, the day-to-day workings of Leviathan, whether constrained by law or its absolute source in the temporal realm, are vulnerable to the intrusions of what Schmitt, sounding somewhat like a surly teenager, calls “real life.” And it is in the state of exception, he maintains, that this power most rudely “breaks through the crust of a mechanism [law] that has become torpid by repetition.”

Why Public Buildings Should Be Beautiful

In the 1920s, the only prominent example Schmitt had before him of what The Economist would now call ‘backsliding’ on liberal democratic norms was Fascist Italy. Quite apart from his character, Mussolini is given credit in The Crisis of Parliamentary Democracy for recognising that politics most galvanises the human spirit when, no longer expecting men to live on procedures alone, Caesar-like figures strive to make an irresistible claim on the masses, achieving a truly democratic identity of ruler and ruled, invariably with the help of spiritually intoxicating myths.

Part of the significance of Italian Fascism, says Schmitt, consists in its repudiation of the more anodyne English model of government: “especially great,” as he puts it, “because national enthusiasm on Italian soil has until now been based on democratic and constitutional parliamentary tradition and has appeared to be completely dominated by the ideology of Anglo-Saxon liberalism.”

Political romance has the inflammatory power to blow apart the most technically sensible template. The dangers of such utopian fever-dreams are well-known and need not be rehearsed. But surely our attachment to romance, in politics as much as in life, needs an outlet? A nation must be anchored by more than the promise of efficiency, particularly if that efficiency—as often seems the case in every newsworthy country besides Bukele’s El Salvador—is nowhere to be seen.

Of course, in Britain the reverence in which Parliament has been held, as much as an aesthetic icon as a reliable institution, makes belief in its rather dull procedures uniquely consistent with an emotional attachment to its grandeur. It is for this reason that all trappings of state should be beautiful. Anything less is a surrender to the sterile cult of utility, a denial of our desire for wonder, a form of cruelty which neglects to integrate deep human needs into the shared symbols that define us. Plus, a nation resistant to having its public life sprinkled with romance—assuming that such a robotic people, beyond the world of etiolated thinktanks, can even exist—is likely sooner or later to find itself drowning in kitsch or drenched in blood.

This connects with a clever remark that the philosopher Tracy B. Strong once made about why Carl Schmitt petrifies the average liberal:“he offends against one of the deepest premises of liberalism: politics is necessary but should not become too serious.” Just as repressing the need for romance in public life risks triggering the kind of grotesque pomp we associate with Nuremberg, there is only so long that a non-serious approach to politics can be indulged while civilisational struggles of supreme importance rage all around us. Liberals would do well to grasp the reality that politics becomes most serious when the questions it thrusts upon us are put off for a date which, though unknowable in advance, may come to live in infamy.

Harrison Pitt is a senior editor at The European Conservative. He co-hosts “Deprogrammed,” a current affairs show produced by the New Culture Forum.